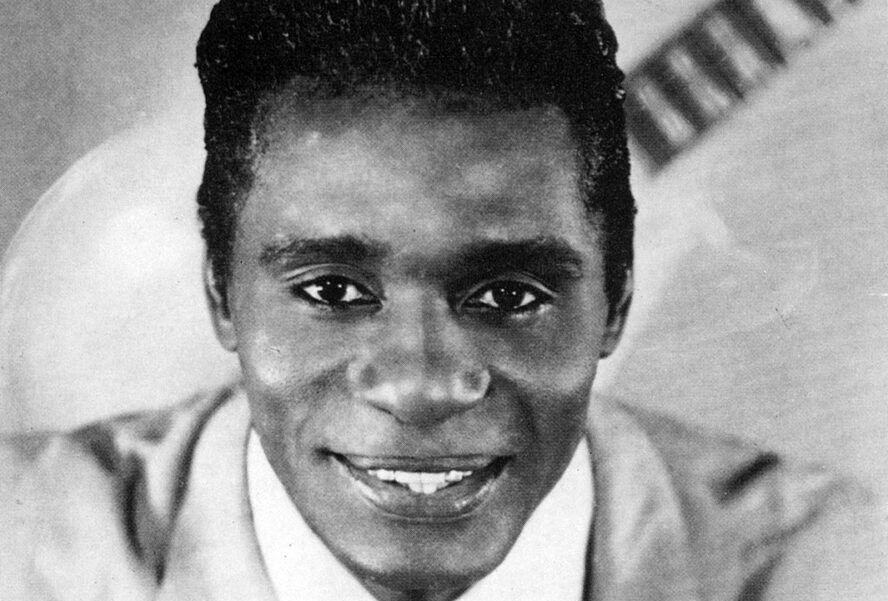

Although he had only a few years in the spotlight, Eddie Lee “Guitar Slim” Jones set a lotfy and influential standard for the pantheon of blues guitarists who would follow him. His signature song, “The Things That I Used to Do,” was recorded in New Orleans in 1954 and became one of the biggest rhythm and blues (R&B) hits of the 1950s. His live performances became legendary for matching bravura musicianship on the electric guitar with outlandish stage antics. He died at the age of thirty-two while on tour in New York, and while he left a limited number of recordings and no video documentation of any of his live shows, he remained for decades among the most influential of guitarists to emerge from the New Orleans R&B scene.

Born in Greenwood, Mississippi, on December 10, 1926, Jones grew up in the cotton fields of the Mississippi Delta around Hollandale, reared by his maternal grandmother, Mollie Edwards, after his mother died when he was five years old. As a teenager he began hanging out in the area’s juke joints, where he occasionally sat in as a singer and attracted notice as a dancer, earning the nicknames “Limber Leg Eddie” and “Rubber Legs.”

At age eighteen he entered military service in the final year of World War II. Upon his discharge in 1946, he returned to the Delta, where blues musician Willie D. Warren took him on as a singer and introduced him to the guitar. Jones performed throughout Arkansas and Louisiana with Warren and Little Bill Wallace before migrating to New Orleans.

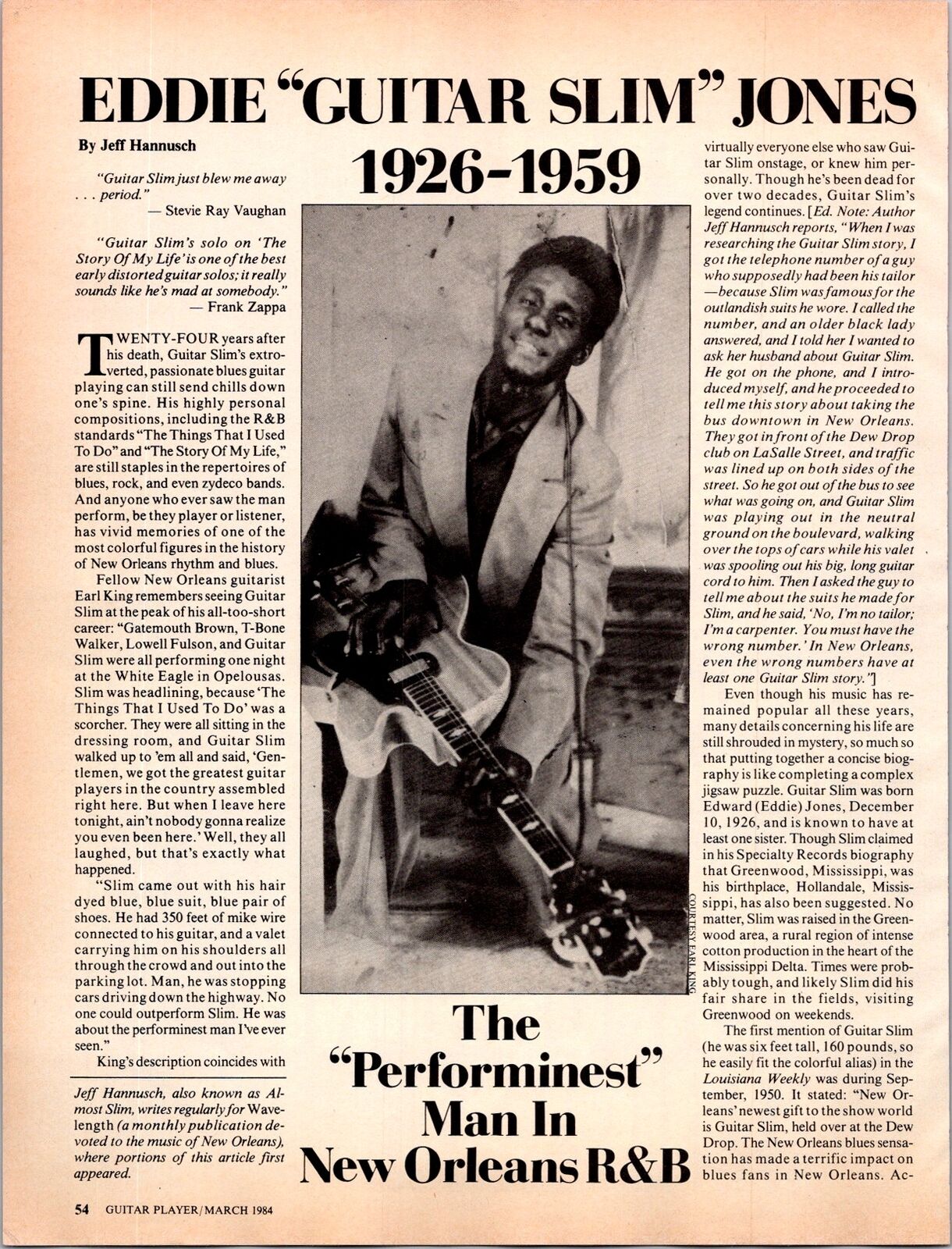

Jones initially performed on the streets and for house parties, but eventually he latched on to several bands as he developed an aggressive guitar style influenced to a large extent by Gatemouth Brown. He began recording for Imperial Records at age twenty-four, about the time he started calling himself “Guitar Slim.” At age twenty-eight he made the enduring hit for which he would be best remembered, “The Things That I Used to Do,” on the Specialty label. It became the biggest R&B hit of 1954 and one of the top R&B records of the 1950s, ultimately selling more than a million records. By then he’d developed an overpoweringly flamboyant persona expressed as both a guitar player and a showman.

“He’d hit the stage carried on the shoulders of his personal valet, wearing a bright red suit and red shoes, his hair dyed to match,” Paul Trynka, former editor of the British magazine MOJO, summarized in 2000. “His guitar playing was the noisiest, dirtiest thing to hit the South, cranked to deafening volume by a huge amplifier rig. … After delivering a vocal in the impassioned, heart-rending style [that] Ray Charles would later take as his template, he’d rush into the audience at the end of a 200-foot guitar cord, playing cranked-up solos all over the club—sometimes with his teeth, sometimes behind his back. Sometimes he’d climb up into the rafters, still playing. At least once, he leapt into a waiting car and soloed until he was out of sight, later walking back onstage to rapturous applause.”

Guitar Slim Live: “The Performingest Man I’ve Ever Seen”

Most fundamentally, Guitar Slim championed the electric guitar as a lead ensemble instrument in the emerging genre of R&B long before any other musician. “Early- and mid-1950s R&B audiences were still accustomed to bands that featured honking saxophones as their primary solo voice fronted by blues singers who kept their guitar work subordinate to the impact of the vocals,” explained historian Robert Palmer, a former popular music critic for the New York Times. “Guitar Slim reversed those priorities.” Moreover, he brought an innate musicality to his approach in bringing the electric guitar front and center, studying primarily Texas-based musicians rather than Mississippi bluesmen prevalent where he grew up. New Orleans songwriter, guitarist, and singer Earl King, who would become something like an apprentice to Guitar Slim as a songwriter, musician, and performer, explained: “He listened to all of ’em and compiled bits of their style—Gatemouth (Brown), T-Bone (Walker), B. B. King. But he took a different approach; he had a lot of melodic overtones in his solos. He used to play a solo that had a marriage to the rest of the song, rather than just playing something off the top of his head.”

Jones also purposely pushed the sonic possibilities of the newly emerging electric guitar to its limits, creating a new sound palette in the world of post–World War II blues and R&B. “Slim was getting a fuzz-tone distortion way before anyone else,” King said. “You didn’t hear it again until people like Jimi Hendrix came along. Believe it or not, Slim never used an amplifier. He always used a public address system, never an amplifier. He was an overtone fanatic, and he had these tiny iron cone speakers—the sound would run through them, and I guess any vibration would create that sound, because Slim always played at peak volume.”

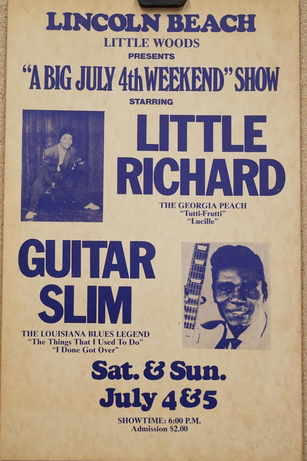

His stage shows, meanwhile, were notorious—and unmatched. “He was the performingest man I’ve ever seen,” King said. “People would drive 200 miles to see him. And he didn’t even have any recordings out when he was drawing these people, which was incredible. Nobody could outdo him onstage, B.B. King, Little Richard, nobody. … He had some kind of magic to him, and to this day I still haven’t figured out exactly what it was.”

Buddy Guy to Jimi Hendrix

But Earl King wasn’t Guitar Slim’s only ardent devotee. A sharecropper’s son from a small town fifty miles north of Baton Rouge, young George “Buddy” Guy made his first instruments from old paint cans and screen-door wire until his father, tired of swatting at swarms of mosquitoes now entering the house, finally bought his son an acoustic guitar with two strings on it. Eventually, while working full time at a Baton Rouge gas station and car wash as a teenager, Guy got the chance to audition for a local bandleader, selecting the big hit of the day, Guitar Slim’s “The Things That I Used to Do,” for his performance, which the bandleader deemed adequate, but decided the performer was much too reserved to work effectively in front of boisterous, barroom crowds. Undeterred, the Louisiana teenager continued to pursue his passion, and when he heard Guitar Slim would be performing at the Masonic Temple in Baton Rouge, “I was the first guy in line to buy a ticket,” Guy recounts in his autobiography, When I Left Home: My Story. “Guitar Slim showed me how to play the guitar in front of people. Whatever he did, I wanted to do. The excitement he caused, I wanted to cause. The pleasure he gave, I wanted to give. I wanted a Strat that I could beat up. I wanted a big crowd that I could drive wild. I wanted to be Guitar Slim.”

Through Guy, then, the sound, spirit, and wild soul of Guitar Slim got translated into Chicago blues and traveled even a step further, influencing Jimi Hendrix. On Hendrix’s double-LP masterpiece, Electric Ladyland, “Come On (Let the Good Times Roll)” was written by Earl King, and historian Robert Palmer says the inclusion of the song is not just a random coincidence.

“Come On,” Palmer wrote, is “a classic, two-part single that, in effect, is the missing link between Guitar Slim and modern rock guitar … an irresistibly funky dance tune highlighted by a riveting, extended guitar solo. King begins playing bluesy lines, more like the Slim we know from records, but he soon begins to stretch up to screaming, liquid, high-note phrases that are uncannily reminiscent of Jimi Hendrix solos recorded less than five years later. There can be little doubt that Hendrix, a veteran of the R&B circuit with stints backing Little Richard and the Isley Brothers, heard ‘Come On’ and took its lesson to heart. Not only did Hendrix build a certain aspect of his style from King’s screaming high-note melisma, he recorded his own versions of Guitar Slim’s ‘The Things That I Used to Do’ and Earl King’s ‘Come On,’ explicitly laying bare the roots of his art. … [And] working the other way, from the watershed of Hendrix’s brief but brilliant career, we can follow this influence into the work of every accomplished rock guitarist working today.”

A Legacy Obscured

As a major R&B star of the mid-1950s, Jones also indulged appetites for drink, women, and the excesses of a star musician’s flamboyant social life. That lifestyle eventually led to a diminished state of health and his untimely death, while on tour in New York City, from bronchial pneumonia at the age of thirty-two. A lack of documentation also helps explain his relatively low profile in the narrative of twentieth-century American popular music—despite recording perhaps a dozen individual songs for three different labels, he never equaled the success or lasting admiration for “The Things That I Used to Do.” In addition, his career was in its infancy just as mainstream R&B, which appealed to mature, Black audiences, was giving way to the rock ‘n’ roll craze of the 1950s, a largely white, teenaged phenomenon. In fact, another factor that obscured the musician’s death was the headline-making airplane accident four days later that took the lives of higher-profile musicians Buddy Holly, Richie Valens, and J. P. Richardson, known professionally as The Big Bopper.

Most critically, perhaps, no evidence whatsoever exists within the arena in which he made the strongest impression: live performance. Even in the digital age, when all previous forms of visual documentation seem to find their way to the Internet, there are no grainy film recordings or early-generation videos of Guitar Slim, not even the audio track of a live performance. Oral history accounts, however, are numerous, and a subsequent, implied line of influence to the foundation of the rock era can be reconstructed fairly easily. But even then, the significance of Guitar Slim’s ultimate legacy is both illuminated and obscured in equal portions by the context of social and cultural history—he pioneered key advances in aspects of twentieth-century popular culture, but it was those who created their own legacies who benefited most from Guitar Slim’s influence. And some historians, such as New Orleans biographer Jeff Hannusch, have made credible claims for Guitar Slim’s having pioneered an entirely new category of music. “Feelin’ Sad,” an early recording, Hannusch says, represents “the first time a blues artist made a record with a spiritual approach. … [It] was a huge influence on Ray Charles, who appropriated the idea of blending blues and spirituals, developing what would become Soul.”

Content provided by 64 Parishes, a project of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities.